November 2, 2022

How does methadone work and why is it needed?

Methadone is a prescription medication and is part of a group of drugs known as opioids. Opioids are depressant drugs, which means they slow down messages travelling between the brain and body.1

Methadone is taken as a replacement for heroin and other opioids as part of a treatment known as pharmacotherapy – which has been around for more than 40 years.1

Pharmacotherapy is when a person replaces their drug of dependence with a legally prescribed substitute. It is often used in conjunction with other treatments such as counselling.

Methadone and buprenorphine are the two main medications used to treat opioid dependence.2

On a snapshot day in 2020, more than 53,300 people received pharmacotherapy at 3,084 dosing points across Australia.2

How do people take methadone?

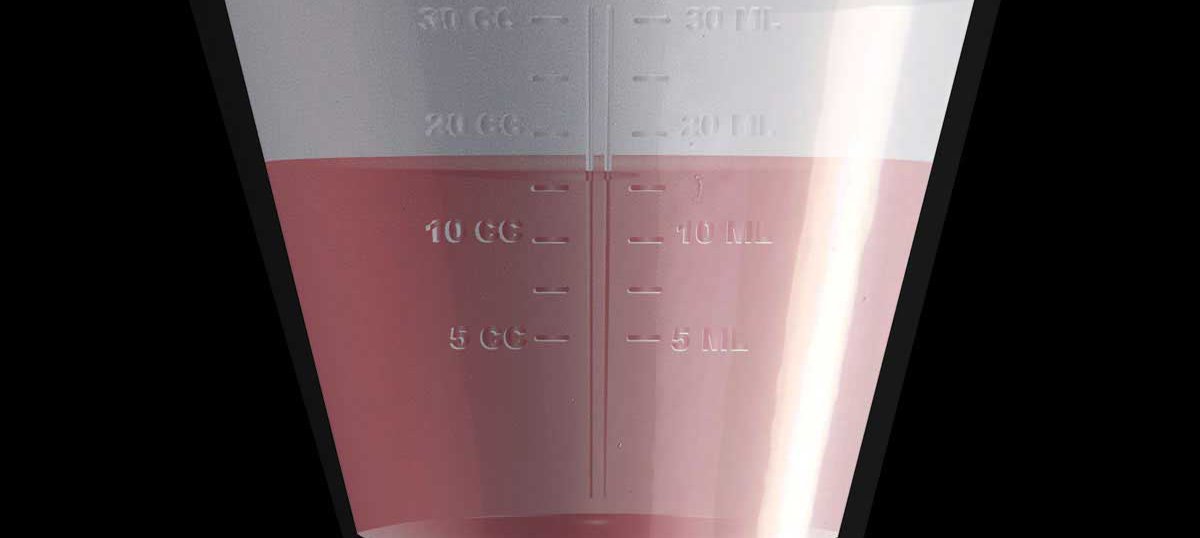

Methadone is only available in liquid form, and there are two main versions used in Australia – Methadone Syrup and Biodone Forte.3

In long-term methadone programs, the person has to attend a public clinic or pharmacy daily to receive their dose. The pharmacist will dilute the methadone liquid with water, and then the person will take their dose and pay a fee for it.

Some people are able to get takeaway doses if the pharmacist decides they are stable on the program and there’s a low risk of the takeaway doses being used incorrectly.

How does methadone help people?

Methadone has the effect of:

- reducing the euphoric (‘high’) feelings of opioids

- reducing opioid withdrawal symptoms

- controlling or eliminating cravings for the opioid the person was dependent on.4

This can support people to focus on things like:

- improving their physical and mental health

- strengthening relationships with friends, family and partners

- finding and maintaining a job.4

It can also help reduce some of the health concerns and risk behaviours that come with opioid use, such as:

- injecting drug use, which increases the risk of blood- borne viruses and other health issues

- chances of overdose

- contact with the criminal justice system. 4, 5

Are there any risks or side effects of methadone?

Health professionals are involved in each stage of prescription, administration and ongoing use – which helps to reduce the potential for risks or negative side effects.4

When first starting a methadone program, a person will work with their health provider to work out the correct dose for them.

This period is called the ‘stabilisation period’ and lasts for about two weeks. During this time, clients are advised not to operate heavy machinery or drive as their body will be adjusting to the medication.6

When a person has an oral dose of methadone, it takes approximately 30 minutes to start being absorbed and reaches peak levels between one to four hours. If a person is on a stable methadone dose and not using other drugs (or withdrawing), their thinking or reaction time shouldn’t be affected.7

Like any other opioid medication, there’s potential for overdose if too much is taken. Overdose is more likely if the person has a low opioid tolerance, or if it’s taken with other drugs.4

If you or someone you know starts experiencing symptoms of overdose, call an ambulance straight away by dialling triple zero (000).

Methadone overdose symptoms might include:

- shallow or slow breathing

- blueish or grey lips/fingertips

- cold, clammy skin

- slow heart rate and chest pain

- falling asleep.1

The prescribing doctor/pharmacist will complete a risk assessment before approving any takeaway doses to ensure a low chance of overdose occurring.

Takeaway doses are an important step for a lot of people as they no longer have to attend a clinic or pharmacy daily. This can be a barrier to getting methadone treatment if they’re living in an isolated area, if they have a busy lifestyle or work and/or family commitments.5

Stigma and the impact of misinformation

Many people accessing pharmacotherapy experience stigma in several different ways, including from:

- family and friends

- employees in pharmacies or clinics where methadone is dispensed

- the community – particularly if the person lives in a small community where there is less anonymity.5

Experiencing any kind of stigma can turn people away from treatment – which means they are unable to get the help they need.

People on methadone programs are the same as anyone else who needs medication to manage a long-term health condition and they shouldn’t be treated any differently.8

Further information and support

To read more on methadone and pharmacotherapy, see below:

- What is opioid pharmacotherapy? - Alcohol and Drug Foundation (adf.org.au)

- Opioid Pharmacotherapy for Young People - Alcohol and Drug Foundation (adf.org.au)

- CHANGING LANES -PAMS | hrvic

If you are looking for information, support or advice regarding methadone or opioid pharmacotherapy treatment, call:

- NSW: Opioid Treatment Line – 1800 642 428

- QLD: Qld Pharmacotherapy Advice & Mediation Service (QPAMS) – 1800 175 889

- VIC: Pharmacotherapy Advice Mediation Support (PAMS) – 1800 443 844

- WA: Community Pharmacotherapy Program – (08) 9219 1907

- Every other state/territory: National Alcohol and Other Drug Hotline (1800 250 015)

- Brands B, Sproule B, Marshman J. Drugs and Drug Abuse. 3 ed. Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation; 1998. Available from: https://adf.on.worldcat.org/oclc/38900581

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Opioid Pharmacotherapy Statistics Annual Data collection Canberra: AIHW; 2021 [cited 2021 May 31].

- Drug and Alcohol Office. Clinical Policies and Procedures for the Use of Methadone and Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Opioid Dependence. Government of Western Australia; 2014.

- Gowing L, Ali R, Dunlop A, Farrell M, et al. National Guidelines for Medication-Assisted Treatment of Opioid Dependence. Australian Government Department of Health; 2014.

- Wood P, Opie C, Tucci J, Franklin R, Anderson K. “A lot of people call it liquid handcuffs” – barriers and enablers to opioid replacement therapy in a rural area. Journal of Substance Use [Internet]. 2019 2019/03/04 [10.10.2022]; 24(2):[150-5 pp.].

- Department of Health and Human Services. Methadone treatment in Victoria. Victoria State Government; 2016.

- Preston A. The Methadone Handbook. Fifth ed. Melbourne: Alcohol and Drug Foundation; 20125. Available from: https://adf.on.worldcat.org/oclc/1128864464

- Rankin J, Mattick, R. Review of the Effectiveness of Methadone Maintenance Treatment and Analysis of St Mary's Clinic, Sydney. University of New South Wales: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre; 1997.