How is tobacco used?

Tobacco is commonly smoked in cigarettes, cigars, hookahs, and pipes. Inhaling the smoke of dried tobacco leaves allows nicotine to be absorbed through your mouth and lungs. When smoked, the effects are usually felt straight away.1

Tobacco can also be chewed, snorted, or held between your cheek and gums. Each of these methods allow nicotine to be absorbed through your nose and mouth. These ‘smokeless tobacco’ products include chewing tobacco, dipping tobacco, snuff, and snus.2

Smokeless tobacco products are not legally available in Australia.4

Nicotine can be consumed in other forms such as vapes. To find out more about the effects of nicotine through vaping, head to our vaping page for more information.

Effects of tobacco

Use of any drug can have risks. It’s important to be careful when taking any type of drug.

Tobacco affects everyone differently, based on:

- size, weight, and health

- whether the person is used to taking it

- whether other drugs are taken around the same time

- the amount taken

- the strength of the drug

- the environment (where the drug is taken).

The effects of tobacco may include:

- increased heart rate

- increased blood pressure

- headache

- dizziness

- nausea

- stomach cramps

- vomiting

- diarrhoea

- reduced appetite

- changed sense of taste

- relaxation

- improved mood

- increased concentration and short-term memory.5-7

People who smoke tobacco regularly may build up a tolerance to the immediate and short-term effects.

Overdose

Smoking tobacco rarely results in overdose effects.8 But, consuming a large amount tobacco in other forms may in result in overdose due to high levels of nicotine.

Call an ambulance straight away by dialling triple zero (000) if you, or someone else, has any of the following symptoms:

- difficulty breathing

- rapid heartbeat

- low blood pressure

- weakness

- hallucination

- seizure.2,9

Long-term effects

Regularly smoking tobacco can increase your risk of:

- sixteen different types of cancers

- stroke

- aortic aneurism (bulging and weakness in the walls of the aorta)

- atherosclerosis (buildup of plaque in the arteries)

- coronary heart disease

- respiratory symptoms (shortness of breath, coughing fits, wheezing)

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (a group of lung conditions)

- lung infections (influenza, pneumonia, tuberculosis)

- eye diseases (blindness, cataracts, macular degeneration)

- periodontitis (bleeding gums, loose teeth)

- diabetes

- hip fractures

- rheumatoid arthritis

- reduced fertility

- ectopic pregnancy or pregnancy loss

- birth defects if the foetus is exposed to cigarettes

- reduced immune function (regular colds and flu)

- overall diminished health (ageing, back pain, slower healing wounds, mood swings)

- dependence on smoking 7,10,11

Smoking ‘light’, ‘mild’, or ‘low tar’ cigarettes does not reduce the harmful health effects of tobacco smoke. Filtered cigarettes also do not protect against smoking-related harms.12

For more information on the long-term effects, visit the Cancer Council.

Passive smoking

Passive smoking occurs when you breath in the smoke of those smoking around you. This is sometimes called second-hand smoke.

No amount of passive smoking is safe.

Passive smoking can cause many of the health problems listed above, and it can also make them worse. It is important not to smoke near other people, especially babies, children, those who are pregnant or breastfeeding, and people with chronic (long-term) respiratory conditions.13

Tobacco and young people

Adolescent brains do not stop developing until the age of 25. During this time, they can be more sensitive to nicotine’s rewarding effects, which can lead to increased tobacco use and dependence. The change in brain development and learning pathways can also increase other reward seeking behaviour and may lead to the use of other drugs or alcohol.14,15

Tolerance and dependence

People who regularly use tobacco can become dependent on nicotine. They may feel they need nicotine to go about their normal activities like working, studying, and socialising, or just to get through the day.

They may also develop a tolerance to it, which means they need to take larger amounts of nicotine to get the same effect.

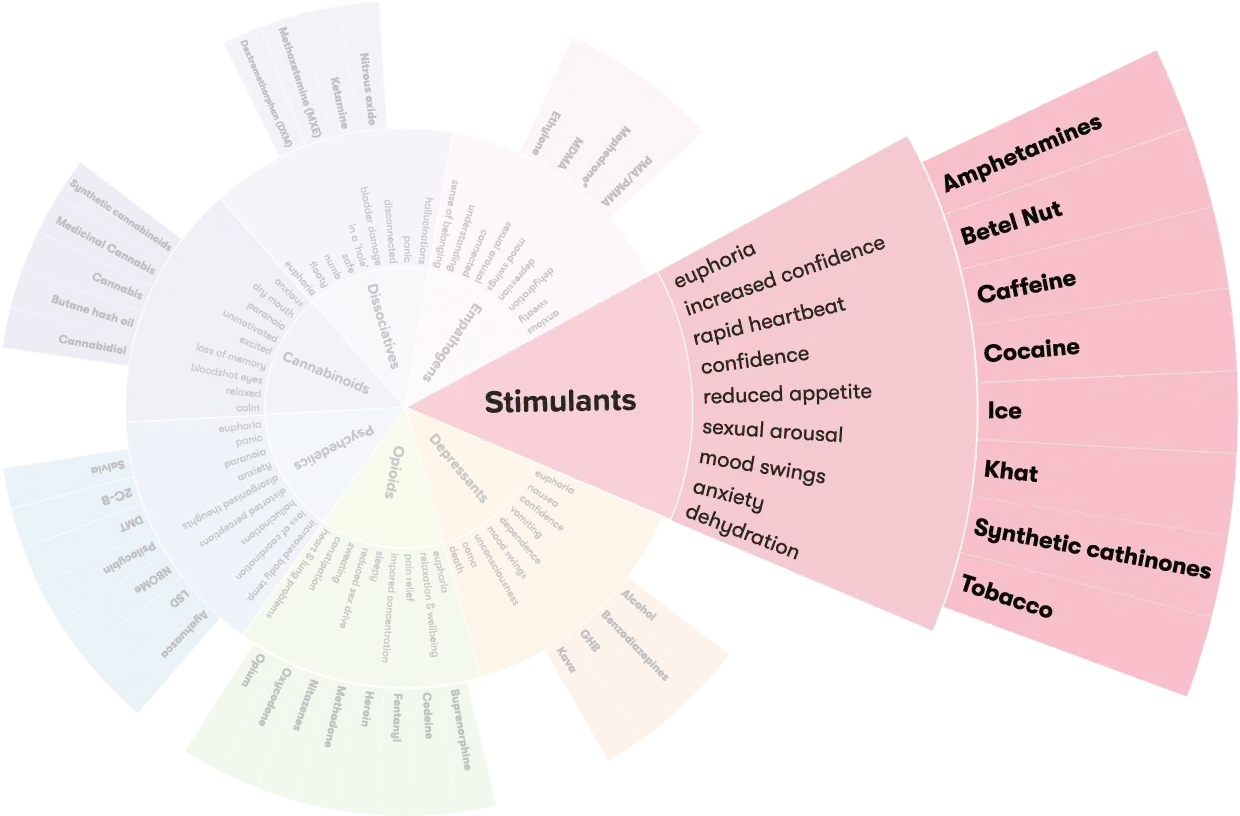

Using tobacco with other drugs

Using tobacco with other drugs can have unpredictable effects and increase the risk of harm.

- Tobacco + alcohol: can increase cravings for nicotine and might cause people who have stopped smoking to start again. You may also feel less intoxicated due to the simulant effect of nicotine, which can lead to drinking more.16-18

- Tobacco + benzodiazepines: reduced effects of benzodiazepines due to nicotine’s stimulating effects.19

- Tobacco + cannabis: increases heart rate, respiratory problems, withdrawal symptoms. Smoking tobacco and cannabis together can increase your exposure to harmful chemicals.20

- Tobacco + opioids (heroin, methadone): may increase the desire and satisfaction of smoking, and lead to smoking more.19

- Tobacco + stimulants (amphetamines, cocaine, ice): increases the stimulant effects and can make smoking feel more rewarding, which can lead to smoking more.19

The use of more than one drug at the same time, or type of drug consumed at the same time, is called polydrug use.2

More on Polydrug use

Polydrug use is a term for the use of more than one drug or type of drug at the same time or one after another. Polydrug use can involve both illicit drugs and legal substances, such as alcohol and medications.

Reducing harm

There are ways you can reduce the risk of harm when smoking cigarettes:

- Do not smoke cigarettes if you are pregnant or breastfeeding.

- Avoid smoking near other people, especially babies and children, those who are pregnant or breastfeeding, and people with chronic (long-term) respiratory conditions to reduce the health harms associated with passive smoking.

- Speak to your doctor about different options for reducing or stopping smoking, including nicotine replacement therapy such as gum or patches.

- Tobacco smoke has the potential to interact with several drugs and medications. Talk with a health professional before starting new medications.

Withdrawal

Giving up smoking after using it for a long time is challenging, because the body must get used to functioning without it.

Withdrawal symptoms usually start within 24 hours after you last use tobacco.21 If you have been smoking for a long time, or if you smoke a lot of cigarettes, you may have withdrawal symptoms as soon as 30 minutes after you last use tobacco.2

Cutting back or stopping smoking might also affect the medications you are taking. It’s important to talk to your doctor when you’re reducing the amount of nicotine in your body.

Nicotine withdrawal may last from a few days to a few weeks. These symptoms can include:

- cravings

- irritability, anxiety, and depression

- restlessness and difficultly sleeping

- increased appetite

- trouble concentrating

- headaches

- coughing and sore throat

- aches and pains

- upset stomach and bowels.2,21

Getting help

Quitting smoking can be challenging but there is help and support available - call Quitline on 13 QUIT (13 78 48).

If your use of alcohol or other drugs is affecting your health, family, relationships, work, school, financial or other life situations, or you’re concerned about someone else, you can find help and support.

Call the National Alcohol and Other Drug Hotline on 1800 250 015 for free and confidential advice, information and counselling about alcohol and other drugs

Help and support services search

Find a service in your local area from our list. Simply add your location or postcode and filter by service type to quickly discover help near you.

If you’re looking for other information or support options, send us an email at druginfo@adf.org.au

Australian Federal and State laws make it an offence to sell or supply tobacco products to people under 18 years of age. It’s also illegal for anyone under 18 years to buy tobacco products.4

Laws also control how tobacco products are advertised, promoted, and displayed in retail shops. Similarly, tobacco products must be in ‘plain packaging’, with no branding, logos, or images except for graphic health warnings.4

In Australia, smoking tobacco is illegal in enclosed public areas such as shopping centres, schools and workplaces, restaurants, and on public transportation.4 Every state and territory has its own set of laws and rules about where you can smoke outdoors. This includes places like beaches, sports venues, playgrounds, and outdoor dining areas.22

It is against the law to smoke in a vehicle when a minor is inside. People under the age of 16, 17, or 18 may be classed as minors, depending on the state or territory legislation.4

See also, drugs and the law.

National

The 2022-23 AIHW National Drug Strategy Household Survey found:

- 1 in 3 (35%) people in Australia aged 14 and over have smoked tobacco in their lifetime.

- Across people aged 14 and over, men were more likely than women to smoke cigarettes on a daily basis (9.0% compared to 7.7%).23

The 2022 ABS National Health Survey Found:

- One in ten adults currently smoke tobacco on a daily basis (10.6% or 2.1 million adults).

- Nearly 30% of adults who previously smoked tobacco have stopped.

- People aged 55-64 were more likely to smoke tobacco daily (15% of adults in this age group).

- Adults living in outer regional and remote Australia were nearly twice as likely to smoke cigarettes on a daily basis than adults living in major cities (16.7% and 9.4%).24,25

Young people

The 2022/23 Australian Secondary Students’ Alcohol and Drug survey found:

- 87% of secondary students (young people age 12-17) in Australia had never smoked.

- 15% of secondary students who have never smoked tobacco are at risk of smoking in the future.

- Half of secondary students that currently smoke tobacco got their cigarettes from a friend.26

The 2022-23 AIHW National Drug Strategy Household Survey found:

- Young people on average smoked their first full cigarette at 16.3 years old.27,28

- Cox S, West R, Notley C, Soar K, Hastings J. Toward an ontology of tobacco, nicotine and vaping products. Addiction [Internet]. 2023 [08.04.2024]; 118(1):[177-88 pp.].

- Darke S, Lappin J, Farrell M. The Pocket Guide to Drugs and Health. La Vergne (US): Silverback Publishing; 2021. Chapter 6, Nicotine & tobacco [08.04.2024].

- Winnall W, Scollo M. 12.2 Other types of tobacco products [Internet]. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2022 [15.04.2024].

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Smoking and tobacco laws in Australia [Internet]. Australia: Commonwealth of Australia; 2024 [03.04.2024].

- Christensen D. 6.10 Acute effects of nicotine on the body [Internet]. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2018 [15.04.2024].

- Christensen D. 6.5 Mood effects [Internet]. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2018 [15.04.2024].

- Christensen D. 6.6 Cognitive effects [Internet]. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2018 [15.04.2024].

- Barbuto A. Nicotine poisoning (e-cigarettes, tobacco products, plants, and pesticides). Burns MM, editor. 2022. [updated 04.2022; cited 20.05.2024]. In: UpToDate [Internet]. Waltham (MA): Wolters Kluwer.

- Alkam T, Nabeshima T. Molecular mechanisms for nicotine intoxication. Neurochemistry International [Internet]. 2019 [16.04.2024]; 125:[117-26 pp.].

- Winstanley MH, Greenhalgh EM. 3.0 Introduction: The health effects of active smoking [Internet]. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2019 [15.04.2024].

- Cancer Council NSW. 16 cancers caused by smoking: Cancer Council NSW; 2020 [cited 2024 12.09].

- Bellew B, Greenhalgh E, Winstanley M. 3.26 Health effects of brands of tobacco products which claim or imply, delivery of lower levels of tar, nicotine and carbon monoxide [Internet]. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2020 [16.04.2024].

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Passive smoking [Internet]. Australia: Commonwealth of Australia; 2023 [15.04.2024].

- Yuan M, Cross SJ, Loughlin SE, Leslie FM. Nicotine and the adolescent brain. The Journal of physiology [Internet]. 2015; 593(16):[3397-412 pp.].

- Castro EM, Lotfipour S, Leslie FM. Nicotine on the developing brain. Pharmacological Research [Internet]. 2023 2023/04/01/; 190:[106716 p.].

- Van Amsterdam J, Van den Brink W. The effect of alcohol use on smoking cessation: A systematic review. Alcohol [Internet]. 2023 [10.04.2024]; 109:[13-22 pp.].

- van Amsterdam J, van den Brink W. The effect of alcohol use on smoking cessation: A systematic review. Alcohol [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Apr 10]; 109.

- Adams S. Psychopharmacology of Tobacco and Alcohol Comorbidity: a Review of Current Evidence. Current Addiction Reports [Internet]. 2017 [10.04.2024]; 4(1):[25–34 pp.].

- Kohut SJ. Interactions between nicotine and drugs of abuse: a review of preclinical findings. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse [Internet]. 2017 [15.04.2024]; 43(2):[155-70 pp.].

- Meier E, Hatsukami DK. A review of the additive health risk of cannabis and tobacco co-use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence [Internet]. 2016 [15.04.2024]; 166:[6-12 pp.].

- The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Supporting smoking cessation: A guide for health professionals [Internet]. East Melbourne (VIC): RACGP; 2019. Chapter 1, Introduction to smoking cessation. [03.04.2024].

- Youth Law Australia. Cigarettes (TAS) [Internet]. Sydney: Youth Law Australia; 2024 [15.04.2024].

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Tobacco smoking in the NDSHS. Canberra: AIHW; 2024 [08.04.2024].

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Smoking and vaping [Internet]. Canberra: ABS; 2022 [08.04.2024].

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Pandemic insights into Australian smokers, 2020-212021 [cited: 16.11.2022].

- Scully M, Bain E, Koh I, Wakefield M, Durkin S. ASSAD 2022/2023: Australian secondary school students’ use of tobacco and e-cigarettes [Internet]. Centre of Behavioral Research in Cancer (VIC): Cancer Council Victoria; 2023 [08.04.2024].

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022–2023 [Internet]. Canberra (AU): AIHW; 2024. Data tables: 2. Tobacco smoking [08.04.2024].

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019 2020 [[08.04.2024].